Historical Significance Narrative -- LAWRENCE's influence IN AMERICA

National Register Nomination for the D.H. Lawrence Ranch

SECTION 8: Narrative Statement of Significance, Continued

7. Lawrence's Influence in America

The formative years of the Taos/Santa Fe art colonies were concentrated between 1900 and 1920 and initially centered on painting. Writers converged on the region shortly after, with Alice Corbin Henderson taking the literary lead in Santa Fe, reflecting her Chicago experience as editor and co‑founder of Poetry, the nation's premier magazine of creative verse. Another pioneer of the literary scene was Harvard‑educated author Witter Bynner, Santa Fe's perennial host and benefactor. Together they filled a social role equivalent to that of Mabel Dodge Luhan in Taos. Both the Taos and Santa Fe colonies were well established and entering their "Golden Age" period by the time of Lawrence's arrival in America. The colonies were enjoying the stimulation from the post‑World War I influx of creative talents drawn to the region's beauty, remoteness, climate, multiculturalism, and history along with its tolerance and support of restless, unconventional artists. Taos was a smaller and more rustic colony, simultaneously dependent upon and competitive with Santa Fe's. Taos had the Indian pueblo while Santa Fe had the Museum of New Mexico and featured better access to transportation via the AT&SF Railway, thus creating two distinct communities with a shared artistic identity. The yearly summer crowd infecting Taos with creative spirit was described by a national magazine: "Artists affect everyone and everyone affects artists, until Taos is now a whirlpool of self‑expression. . . . All Taos is art conscious" (Arrell Morgan Gibson, 63).31

Lawrence is prominently linked with the development of the Taos region in general reference books and travel guidebooks. Even the Taos County Chamber of Commerce Webpage proudly presents this Lawrence quotation as motto: "You cannot come to Taos without feeling that here is one of the chosen spots on Earth" (Taos Chamber of Commerce Website). His contribution to the Taos/Santa Fe artist and writer colonies was significant due to the number of contacts he made while living in New Mexico. These include the poet, Bynner (who wrote of his experiences in Journey with Genius: Recollections and Reflections Concerning the D.H. Lawrences); the editor of the Laughing Horse literary journal, Willard Johnson (who published a special issue dedicated to Lawrence); the Danish painters, Kai Gotzsche (who painted Lawrence's portrait and provided cover‑art for Lawrence's translation of Giovanni Verga's Mastro‑Don Gesualdo) and Knud Merrild (who wrote A Poet and Two Painters: A Memoir of D.H. Lawrence and produced cover‑art for Lawrence's story collection The Captain's Doll in addition to portraits of him); journalist, Joseph Foster (who wrote D.H. Lawrence in Taos); and Mabel Dodge Luhan (who wrote Lorenzo in Taos).32 Lawrence was also acquainted with some of the important founding members of the Taos colony: Walter Ufer and Victor Higgins (both were among the original Los Ochos Pintores which formed the Taos Society of Artists in 1912 to promote critical recognition and marketing), Leon Gaspard (a renowned Russian artist), and Andrew Dasburg (one of the most influential painters in both the Santa Fe and Taos colonies). Ufer, Gaspard, Foster, Johnson, and Mabel Luhan all made visits to the ranch in the summer of 1924. The actress Ida Rauh saw the Lawrences at Kiowa Ranch in May of 1925 to read over his play David. And Willa Cather, a regular summer visitor to Santa Fe, came to Kiowa in July of the same year. She described the Lawrences as "very unusual, charming, and thrilling people" (as in Ellis, 354). Soon after, Cather would write Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), portraying Catholic pioneers in the Southwest. Another Santa Fe luminary introduced to Lawrence was Mary Austin, an author and Indian rights activist. Even before Lawrence's arrival in America, the New Republic lumped them together as being leaders of the "Back to Montezuma" school of "primitivism" because of their stated sympathies for Native Americans. They both had critiqued modern culture by invoking Indian folk art and lore.

In addition, Lawrence was responsible for importing the considerable talents of the Honorable Dorothy Brett, an alumna of the Slade School of Art in London. Brett permanently settled in Taos, eventually becoming an American citizen. Her memoirs, entitled Lawrence and Brett: A Friendship (1933), is a valuable diary-like source on ranch activities and cabin description. She produced cover‑art for the original U.S. editions of Lawrence's The Boy in the Bush (1924) and The Plumed Serpent, the latter painting created at the ranch in the spring of 1925 (see Appendix Q). Her portraits, including several of Lawrence, and her distinctive paintings of Indian ceremonials have earned considerable repute, many being displayed in major American and European museums.33 She claimed it was her goal to "paint the inner life of the Indian . . . his reverence for the earth, the world that feeds him and keeps him alive" (Morgan, 54). As a Lawrence devotee, Brett transferred his symbolic "vitalism" into the visual medium. Her large painting entitled The Kiowa Ranch (produced on‑site in 1925), with the collaborative addition of figures made by Lawrence and Frieda (Appendix B), hangs in the exhibition "Lawrence's Women" at the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos accompanied by other works by Brett, Frieda, and Mabel. A selection of Lawrence's own paintings was acquired by Saki Karavas (now deceased), the former proprietor of the La Fonda Hotel that is located on historic Taos Plaza; and the showing is advertised by an outside wall plaque.

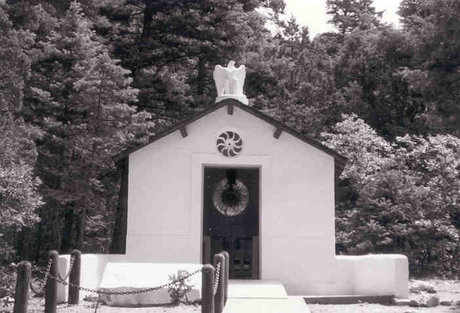

Lawrence's significance can likewise be traced forward to artists drawn to northern New Mexico later. In 1929 Georgia O'Keeffe spent several weeks at the Kiowa Ranch and was inspired by the stately pine outside the Lawrence cabin to paint The Lawrence Tree as seen looking up through the branches at a starry sky (Appendix I). Aldous and Maria Huxley stayed the summer with Frieda at Kiowa Ranch in 1937, and there Huxley completed his Ends and Means (1937). He previously had used local terrain for a scene in Brave New World (1932) and modeled the character of Rampion in Point Counter Point (1928) after Lawrence. Mississippi‑born playwright Tennessee Williams was another visitor to see Frieda and the memorial in August of 1939. He was so moved by the experience that he started drafting I Rise in Flame, Cried the Phoenix a few days later as a direct result of the trip. The one‑act play centers on the final days of Lawrence's life. Williams later wrote with Donald Windham an adaptation of Lawrence's short story "You Touched Me"‑‑a comic play which was revised several times in the 1940s. According to Williams's biographer, Donald Spoto, "there can be no doubt of Lawrence's influence on Williams's early prose and poetry‑‑particularly regarding the mystic confluence of sex, nature, and power" (74). Also in 1939 the poet W.H. Auden rented Lawrence's cabin from Frieda (describing her as the "original Earth‑Mother") and in 1940 adapted Lawrence's short story "The Rocking‑Horse Winner" for radio. In June and July of 1941 Richard Aldington, the Lawrences' friend and author of the book D.H. Lawrence: Portrait of a Genius, But..., visited and collected a set of Kiowa Ranch butterflies which he offered to share with Frieda (Frieda Lawrence and Her Circle, 85). The poet Stephen Spender spent the summer of 1948 at Kiowa Ranch where he wrote much of his autobiography, World Within World (1951). The conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein stayed a week the same summer and worked on his second symphony, The Age of Anxiety (based on the work of Auden), using Frieda's old upright piano. The popular conductor Leopold Stokowski was another among the numerous talented individuals who made the pilgrimage to the ranch.

Many American writers, besides those already named, have felt compelled to study, write about, and pay homage to Lawrence and his works. Poet William Carlos Williams wrote "An Elegy for D.H. Lawrence" in which he laments: "Poor Lawrence/ worn with a fury of sad labor/ to create summer from/ spring's decay" (Williams, 64‑67).34 H.D.'s poem "The Poet" is thought to be a tribute to Lawrence with its "shrine so alone" in the desert: "everyone has heard of the small coptic temple,/ but who knows you,/ who dwell there?" (Collected Poems, 465).35 She also wrote the novel Bid Me to Live: A Madrigal (1960) as a debate with Lawrence through her characters of Julia and Rico. Author Norman Mailer wrote The Prisoner of Sex (1971), providing a rhetorical defense of Lawrence against early feminist attack during the heat of the sexual revolution. Anais Nin wrote a sensitive examination of Lawrence's works entitled D.H. Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study (1932, 1964), a book which is thought to have matured her as a writer. The scholar Harry T. Moore made the following observation in the 1964 introduction (reprinted 1994):

The particular kind of intuition‑‑emotional knowledge‑‑for which we are so grateful in Miss Nin's own later fiction, she first applied to her explication of Lawrence. Surely this book was an important stage in her own development. . . . And what she so wonderfully knew in youth, and could see in Lawrence's writings, is still very valuable, valuable to all of us. (12)

Henry Miller became almost obsessed in his study of Lawrence's mystical philosophy while writing The World of D.H. Lawrence: A Passionate Appreciation (1980). He described his sense of commitment by saying: "The only way to do justice to a man like that, who gave so much, is to give another creation. Not explain him‑‑but prove by writing about him that one has caught the flame he tried to pass on" (Letters to Anais Nin, 117).36 Miller believed that Lawrence's essays embodied many of the intellectual ideas that he himself was trying to forge in his own works. What started as an assignment to put his "competition" behind him led to a lifelong fascination with, and esteem for, Lawrence's genius. Pulitzer Prize‑winning author Bernard Malamud incorporated his interest in Lawrence's life into his novel, Dubin's Lives (1979), dealing with the love and marriage of a biographer who has selected Lawrence as his current subject. Critic Eugene Goodheart remarks, "Dubin's Lawrence speaks to the troubled domestic lives of Americans in the middle of the century" (Legacy, 150). Joyce Carol Oates, who shared Lawrence's humble, working‑class upbringing, wrote The Hostile Sun: The Poetry of D.H. Lawrence (1973) in praise of his writing and philosophy. She pointed to the "protean nature of reality" revealed in his works and how he discerned "a pattern of harmony and discord, which is Lawrence's basic vision of the universe and the controlling aesthetic behind his poetry" (12, 20).

Lawrence's legacy to other American writers and especially poets has been considerable, as his successors attest. Jeffrey Meyers asserts that "his art has survived through association and transmission" across a broad spectrum (Legacy, 2). Karl Shapiro has stated that Lawrence was a very "American" writer and called him "one of the few moderns who really understood Whitman and learned from him. . . . Lawrence taught everybody the best free verse and the brightest imagery in the clearest of voices . . . ."37 In answer to the age‑old question of what one book of poems to take to a desert island, Shapiro chose Lawrence's, ultimately referring to Lawrence as the "god of letters" ("The Unemployed Magician," 378‑395). Theodore Roethke created some of his poems after the fashion of Lawrence's Birds, Beasts and Flowers in which no creature is too small or unworthy of notice. He acknowledged his profound debt shortly before death: "In terms of immediate influence, I read a lot of Lawrence's prose, almost all of it."38 Robert Bly expressed his gratitude: "those masterly generous acts of attention that we call D.H. Lawrence's poems lie underneath all my 'Morning Glory' and seeing poems."39 Knowledge of Lawrence's works helped to shape Bly's organic theories on poetry. Galway Kinnell favored the "otherness" and "mystery" represented in the animal and love poems, hailing Lawrence "among the great germinal poets of modern times" (54). Kenneth Rexroth borrowed from Lawrence's example of emotional force and frank personal style for his own love poems. He remarked in his Introduction to Selected Poems of D.H. Lawrence that the "accuracy of Lawrence's observations haunts the mind permanently" (11). Gary Snyder discovered Lawrence in high school and considered him one of his greatest teachers:

I have a great respect for Lawrence. . . . [S]omebody was passing around a copy of Lady Chatterley's Lover‑‑wow . . . I thought: I would like to read some more of this fellow. So I went to the Public Library and I found Birds, Beasts and Flowers listed in the catalogue. I read the book and I said: This man knows what he is talking about, and I was converted to the poetry right there, and to modern poetry. (Towards a New American Poetics, 119)

Robert Creeley, exasperated with the tone of "deadness" spread by T.S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land, wrote to Charles Olson, "Lawrence is worth 50,000 Pounds in any market,"40 and in another letter, "I love, again, that man, still, the most" (Creeley, 2:126, 3:99). Even the young Robert Frost was enthusiastic about Lawrence's poetry, writing to Edward Garnett in 1915: "I'll tell you a poet with a method that is a method: [D.H.] Lawrence. I came across a poem of his . . . and it was such a poem that I wanted to go right to the man that wrote it and say something" (Frost, 179). The well‑read Lawrence was adept at absorbing literary traditions and making them uniquely his own, thus influencing poets with a wide range of styles from "high" to "low." For example, Robert Lowell, who praised Lawrence for his free verse (Lowell, 124), shifted from elaborately formal early poetry to supple free forms, reminiscent of Lawrence's, while the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg gained from Lawrence's rhythmic control and sharp detail as well as his bold experiments in form. As one critic points out, "Lawrence showed American poets how to write as individuals fully alive in thought and feeling, at all times responsive to the passing moment" (Roberts W. French, 134).

Evidence of Lawrentian inspiration and influence can also be seen woven into the works of modern women writers. Both Amy Lowell and Harriet Monroe were strong supporters of Lawrence and furthered his career in America. Lowell welcomed him as an "Imagist" poet by including his poetry in her anthologies and sent him gifts of money and a typewriter; Monroe published his poems in Poetry magazine. Pultizer Prize‑winner Marianne Moore declared it "an eager delight" (249) to accept his poetry for publication in the Dial during her reign as editor 1925‑1929. Sylvia Plath recorded in her journals that Lawrence was one of her two great teaching masters. According to a biographer, she named her first child Frieda both for a relative and for Frieda Lawrence, whom she admired (Wagner‑Martin, 174). Eudora Welty has said of Lawrence (in The Eye of the Story): "He is first wonderful at making a story world, a place, and then wonderful again when he inhabits it . . ." (97). Critic Carol Siegel notes the fluidity of both Lawrence's and Welty's fiction in representing female desire and how they follow the same mythic traditions: "The specific myths she chooses to rework and her fondness for sun imagery are strongly reminiscent of Lawrence's texts" (166). Welty's story "At the Landing" is frequently compared to Lawrence's novella The Virgin and the Gipsy and cited as a prime example of the Lawrentian imagery prevalent in her work. Kay Boyle wrote that Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature gave her "a singular courage" as a writer (16); this led her to his other works, such as St. Mawr, which then echo in her own writing.41 Lawrence's influence can also be traced in Elizabeth Bishop, Denise Levertov, Adrienne Rich, Carson McCullers, and Meridel LeSueur (to limit the list strictly to Americans).42 Women's literature both recognizes Lawrence's contribution in portraying female issues and is at the same time ambivalent, borrowing from Lawrence and sometimes reacting against him in creative dialogue. Despite Lawrence's veneration for the "living male power," Sandra Gilbert observes: "Over the years, I've noticed that women students are often especially drawn to this writer's work, as if . . . they sensed something quasi‑feminist in it" (“Preface,” xii).

On the academic front, Lawrence continues to evoke new lines of study among scholars. As suggested above, feminist critics, in revisionary studies, have vigorously interrogated Lawrence's views on women (like Kate Millett) and have located him historically within the debates over the early women's movement in England (Hilary Simpson); more recently they have even placed him within a women's literary tradition (Sandra Gilbert, “Preface”; Siegel).43 Gender studies examine the roles of men and women in their various interrelationships as portrayed in Lawrence's fiction. His focus on nature is highly relevant to an age that places emphasis on ecological awareness (as in Dolores LaChapelle's Future Primitive of 1996). Lawrence's fiction aptly lends itself to psychological approaches due to the Oedipal themes that stand out in some works like Sons and Lovers, in particular. Lawrence studies have kept pace with the shifts in psychological criticism as his works have been filtered through Freudian, Jungian, Lacanian, Kleinian, and even Deleuzian (anti‑Oedipal) interpretations.44 In 2001 the Modern Language Association of America issued Approaches to Teaching the Works of D.H. Lawrence, ed. Elizabeth Sargent and Garry Watson, containing more than 30 contemporary approaches to Lawrence in the classroom. His international standing also remains high, as shown in The Reception of D.H. Lawrence Around the World (1999), edited in Japan by Takeo Iida with esteemed contributors from East and West. In an obituary the Manchester Guardian claimed, "Mr. Lawrence was a writer who has exercised a more potent influence, perhaps, over his generation than any of his contemporaries."45 As one of the most widely studied authors of the 20th century, he extends his influence into the future.

Perhaps the largest impact Lawrence had on American policy was the result of the "Lady ChatterleyTrials" that virtually abolished state censorship and upheld the freedom of speech for literature, thus contributing to the national pendulum's swing toward legal and social liberalism (particularly during the 1960s and 1970s).46 Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928) had been under ban, disturbing the public watchdogs on several accounts: inter‑class relationships, adultery, divorce, explicit sexual scenes, and particularly certain four‑letter words that Lawrence had attempted to purge of their "dirtiness" by placing them in poetic contexts. During the U.S. Supreme Court trial held in 1959, Grove Press defended Lawrence against the Postmaster General's charge of "obscenity" by establishing the novel's "redeeming social importance," which then allowed the book to be shipped through the U.S. Postal Service (Rembar).47 The American victory acted as a contributing catalyst for the 1960 London case of Regina v. Penguin Books, which also supported the literary merit of Lady Chatterley's Lover. Penguin, a publisher of mass‑market paperbacks, won the right to reprint a thirty‑year anniversary edition of Lawrence's works, including this last, most controversial novel. The book was legitimized for a third time in 1962 by a similar Supreme Court of Canada trial involving the unexpurgated New American Library edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, which elicited positive testimony from leading Canadian writers and scholars (Nause, 198‑202). After the Chatterley trials, an estimated 10,000,000 copies of Lawrence's books were sold world‑wide in less than a decade, confirming Lawrence's far‑reaching international influence (Jackson and Jackson, 11). The general engagement with Lawrence can best be accounted for by this passage from one of his 1925 letters: "I can't bear art that you can walk around and admire. . . . An author should be in among the crowd. . . . [W]hoever reads me will be in the thick of the scrimmage, and if he doesn't like it‑‑if he wants a safe seat in the audience‑‑let him read somebody else" (Letters 5:201). Lawrence challenges readers and writers to think, thus continuing to have relevance to society today.

Narrative by Tina Ferris & Virginia Hyde

(2004)