Historical Significance Narrative -- FRIEDA'S RANCH YEARS

National Register Nomination for the D.H. Lawrence Ranch

SECTION 8: Narrative Statement of Significance, Continued

6. Frieda's Ranch Years

Lawrence [in his later years] went on to produce other memorable works including his Last Poems(1932), Etruscan Places (1932), Apocalypse (1931), The Virgin and the Gipsy (1930), The Man Who Died(1929), and his most widely known novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928). His passion for writing continued until his death on March 2, 1930, at the age of 44. He was buried in Vence, France, with a simple ceremony attended by Frieda, her daughter Barbara, the Aldous Huxleys, Achsah Brewster, Ida Rauh, and a few others. Frieda commissioned a headstone made of pebbled mosaic in the design of a phoenix. However, she wrote to Bynner a week later stating her ultimate wish to transport Lawrence's body back to Kiowa Ranch: "Now I have one desire‑‑to take him to the ranch and make a lovely place for him there. He wanted so much to go" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 235).

Frieda arranged for her new Italian companion, Angelo Ravagli, to escort her to America; and they stayed at the ranch, inspecting its condition, from June to November of 1931. Janet Byrne claims in her biography that Frieda spent much of her time at the Lobo [Kiowa Ranch] trying to coax memories of Lawrence onto paper" (Byrne, 360). It was in the old cabin that Frieda produced her book about life with Lawrence, "Not I, But the Wind...," a phrase from the first line of one of Lawrence's poems celebrating their love and interconnectedness. Meanwhile, Ravagli cleared the ranch of accumulated scrap and made plans for a larger cabin that was to have cold running water, electricity, and“especially a big kitchen”(Aldington, p. 179; Squires & Talbot, 375). Frieda later recreated Ravagli's attitude toward the old "upper ranch" in her autobiography:

'I will build a house, a house fit to live in, not an old cow‑shed like this one but a fit place for human beings to live in. Here the packrats are running overhead like elephants and the chipmunks will soon drive us out. Get a string and show me where you want your new house and how big you want it.' (Memoirs and Correspondence, 28)

First, however, legal issues regarding Lawrence's estate required Frieda to return to England for the probate hearing which finally decided in her favor and secured her financial independence. (Lawrence had unfortunately died without updating his will, which had become lost in the various moves, and two of his siblings had thus attempted to claim a share of the inheritance.) Frieda and Ravagli arrived back at the Kiowa Ranch on May 2, 1933, and began almost immediately to lay the foundation of the new log cabin. During this time, Frieda completed the final draft of "Not I, But the Wind...," including many of Lawrence's early letters she had found in her mother's desk in Germany. The book was published in October of 1934 with favorable reviews, rating her book above the horde of others produced by friends and acquaintances soon after his death. Frieda is also credited with penning the most poignant epitaph: "What he had seen and felt and known he gave in his writing to his fellow men, the splendour of living, the hope of more and more life . . . a heroic and immeasurable gift" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 106).

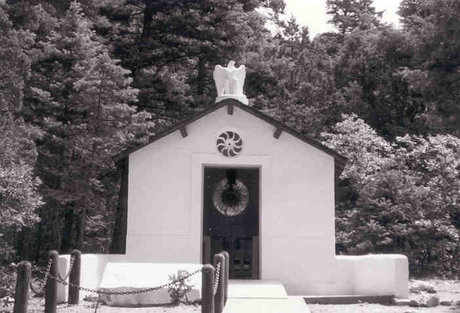

On the fifth anniversary of Lawrence's death (March 1935), Frieda sent Ravagli to Vence to retrieve Lawrence's remains. Ravagli had built at the ranch the simple, chapel‑shaped memorial high on a hill with a spectacular view of the desert. Frieda had formed the idea for the shrine while visiting the British Museum in London and experiencing the peaceful ambiance of its Egyptian exhibit. After Lawrence's body was exhumed and cremated, the ashes were brought back to New Mexico along with a controversy bordering on the comic.28 Some versions of the story say Lawrence's ashes were accidentally spilled or purposely dumped and then replaced with fireplace ash; others say they were eaten in chili or stirred into tea. The urn and its contents were forgotten and retrieved several times enroute from New York to the ranch, and plans by Mabel and Brett to steal the ashes and scatter them over the desert were foiled by Frieda's counter‑plan of either mixing the ashes into the concrete or cementing them behind the altar of the newly‑built shrine. The confusion and possessiveness over the ashes add a touch of mystery to the transfer, and as biographer Brenda Maddox writes: "This ambiguity of resting place gave rise to the sense that Lawrence was nowhere and everywhere" (501).

Frieda was outspoken in promoting and defending Lawrence's literary talents after his death. Her unique perspective as the "wife of D.H. Lawrence" was continually being sought. When the Dial Press decided to publish in 1944 The First Lady Chatterley (an early version of his last novel), Frieda was asked to write the foreword. In it she calls the novel "the last word in Puritanism" since only "an Englishman or a New Englander could have written it." She ends by hailing Lawrence's integrity: "He never wrote a word he did not mean at the time he wrote it. He never compromised with the little powers that be; if ever there lived a free, proud man, Lawrence was that man" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 456). Her own strength of character is reflected in these lines from her autobiography: "Whatever happens to me, good or ill, however people hurt me one way or another, I won't let my blood turn sour and my spirit grow resentful" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 20). Frieda corresponded with many of the Lawrence scholars of her day and tactfully answered their questions; these included E.W. Tedlock, Jr., who wrote the descriptive bibliography of manuscripts in her possession, The Frieda Lawrence Collection of D.H. Lawrence Manuscripts (1948) and also Harry T. Moore, whose biography of Lawrence, The Priest of Love, was first published in 1954 as The Intelligent Heart. Over the years, she also made astute observations like this one from a letter to English scholar Edward Gilbert regarding Lawrence's prolific and enigmatic nature:

Lawrence wrote like a tree puts out leaves and grows tall and spreads. It was not a cerebral conscious activity. That was his genius. . . . He did not nail things down, but left the door open for others to come along. He was great enough to know that life goes on and there is no ultimate word. (Memoirs and Correspondence, 343‑344)

Referring to the couple's infamous quarreling, Frieda dismisses conflict as "natural" between two people of dominant personalities who love each other with intimacy and frankness. Furthermore, she provided counterbalancing opposition to keep his novels from being, in Lawrence's term, "too much me." Frieda maintains that Lawrence "always listened to her, even when he was angry" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 130).

She expanded Lawrence's perspective by bringing him into contact with German high‑culture and the innovative sociological and psychological ideas then being espoused by Max Weber (the epitome of Heidelberg enlightenment), Sigmund Freud, and his disciple Otto Gross (with whom Frieda had a brief pre‑Lawrence love affair). Frieda claims she was "full of undigested theories" at the time she met Lawrence ("Not I, But the Wind...," 3). One of the first conversations she shared alone with him had centered on Oedipal themes, which are played out dramatically in Sons and Lovers; and, as a result, Lawrence revised the novel to accommodate his new understanding.29 Worthen believes that the revision of Sons and Lovers was "Frieda's most important contribution to his writing" and that afterward "Lawrence would constantly return to the theme of men and women (but especially women) breaking away from their security and risking themselves in their bid for self‑fulfilment" (Early Years, 446).

The German erotic movement, to which Frieda had been introduced, was initiated as a rebellious response to the overpowering Bismarckian patriarchy. Gross's ideas had been shaped in part by a group of Bohemian intellectuals active in Schwabing around the turn‑of‑the‑century known as "The Cosmic Circle" (die kosmische Runde), who built upon the matriarchal concepts of the Swiss anthropologist J.J. Bachofen, author of Mother‑Right (1861). Cultural historian Martin Green describes their beliefs: "They stood for life‑values, for eroticism, for the value of myth and primitive cultures, for the superiority of instinct and intuition to the values of science, for the primacy of the female mode of being" (73). These ideals, and others such as "blood‑consciousness," were in tune with Frieda's basic personality and, through her, contributed to Lawrence's own philosophy and fiction. Frieda's relationship with Gross in 1907 had been liberating to her at a time when she felt stifled, thus helping to establish her self‑identity and sexual confidence. However, she recognized the danger of his extreme and radical idealism. As she later wrote, "something was wrong in him; he did not have his feet on the ground of reality" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 102). She preferred the stability of the more responsible and conservative artist‑rebel born of the working classes. Theory was thus tested in the crucible of the Lawrences' shared life experience, but within the traditional framework of marriage. The young and curious Lawrence responded enthusiastically to Frieda's foreignness, like a much needed breath of fresh air, calling her "the most wonderful woman in all England" and "the woman of a lifetime" (Letters 1:376, 384). Frieda later confessed to the added challenge of bridging the gulf between English and German upbringing‑‑"beyond class there was the difference in race, to cross over to each other," she wrote: "Only the fierce common desire to create a new kind of life, this was all that could make us truly meet" ("Not I, But the Wind...," vii). Frieda considered it her task and responsibility to release Lawrence from his "British" inhibitions, thereby freeing his creative talent and helping him to "flower."

Although the degree of Frieda's influence on Lawrence's writing is still hotly debated, it is generally agreed that she was an integral part of his life during their eighteen years together. Biographer Rosie Jackson says of Frieda's contributions throughout Lawrence's career:

She continued to offer criticism, ideas, support and stimulus. She constantly read his work and gave vigorous feedback. She encouraged him to extend his imaginative range, to take risks, to move into new areas with his fiction, to be more direct. . . . In these and other ways, Frieda was an essential part of Lawrence's imaginative process. His creative projection went from him to her and back before it entered his writing. She is also one of the most constant features in his imaginative landscape. As if Lawrence were sustaining an inner dialogue with her throughout his fiction, Frieda appears in work after work. (63‑64)

Consequently, Frieda has since served other writers as a model for fictional characters in the role of a "goddess of Eros" or a life‑affirming Magna Mater (as in Aldous Huxley's The Genius and the Goddess, for example). According to her own biographer, "Frieda's face has been the unseen heraldic sign on the flyleaf of hundreds of works" (Green, 338). She refused to be reduced to those mythic archetypes alone, however, and defended herself by saying to a critic, "You belittle him [Lawrence] if you think I was just a passionate female to him and rather dumb" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 333). Lawrence called her special gift a "genius for living," and Frieda claimed that "the chief tie between Lawrence and me was always the wonder of living . . . every little or big thing that happened carried its glamour with it" ("Not I, But the Wind...," 36, 70).

Frieda enjoyed being a patron of the arts and soon became a valued member of the Taos community. Among her friends were Millicent Rogers (Standard Oil heiress and Mabel's successor as cultural hostess in Taos), Rebecca James (secretary of the Harwood Foundation in Taos), and Georgia O'Keeffe (artist and wife of Alfred Stieglitz). O'Keeffe described her first impression of Frieda in 1934:

I can remember clearly the first time I ever saw her, standing in a doorway with her hair all frizzed out, wearing a cheap red calico dress that looked as though she had just wiped out the frying pan with it. She was not thin, not young, but there was something radiant and wonderful about her. (Feinstein, 250)

Of her ranch gatherings and "down‑home" cookouts, Byrne states, "Frieda's tastes were understated and egalitarian. . . . Hot dogs and pots of chili preceded hand‑cranked ice cream, and artists rubbed elbows with the titled and high‑ranking" (383). Byrne continues, "To a younger generation of writers, artists, and musicians, many of whose careers she had helped cultivate and finance, she was something of a retired diva" (412). Her free time was spent on embroidery, knitting, and painting. One watercolor, preserved at the University of Texas, depicts Lawrence as St. Francis with birds and fishes in a Tyrolian setting, reflecting Frieda's Germanic roots and her religious upbringing.30 The Kiowa cabins were decorated in the style of Bavarian summer cottages. She also kept the Lawrence Memorial supplied with fresh pine boughs and graciously welcomed visitors at the Kiowa Ranch. Claire Morrill, longtime Taos shopkeeper and author of A Taos Mosaic, relates her memories of Frieda's broad smile and guttural laugh and how she had a "way of building someone's bit of small talk into something important and unobtrusively giving it back to him as his own" (118). Morrill adds, "There were few who knew her in Taos who did not really love her" (121). Frieda's joyous nature is reflected in a 1951 letter to an old friend: "I wake up in the morning and the sun rises on my bed and I run around the house happy and grateful to be alive (this is a morning country). I love doing what I do. . . . I am a lucky old woman!" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 342)

In 1938 Frieda bought the Los Pinos house (just north of Taos in El Prado) to escape the cold winter months on Lobo Mountain. She writes to her son, Monty, in August of 1939, "We will have a bathroom and lots of water in Los Pinos" (Memoirs and Correspondence, 275). There was also a workshop big enough to hold a kiln for Ravagli's ceramic work. As Frieda got older, she spent less time at the ranch and began making arrangements with the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque to take it over. Frieda and Ravagli were married on Halloween of 1950 by a Justice of the Peace in Taos, thereby entitling him to half of her remaining estate. In November of 1955, she deeded the Kiowa Ranch property to the university with explicit instructions that ten acres be maintained and left open to the public as a "perpetual memorial," a mecca for unpublished writers and others (Appendix T-T3). Her gift to the university was accepted by resolution of the Board of Regents at a meeting held on November 19, 1955 (Appendix U-U2), and has since been known as the "D.H. Lawrence Ranch."

Frieda's unfinished autobiographical novel, "And the Fullness Thereof," was published posthumously in 1961 within Frieda Lawrence: The Memoirs and Correspondence. In it she writes how Lawrence "walked into her life, naturally and inevitably as if he had always been there, and he was going to stay" (104). She compares her full life to the diversity of nature surrounding her at the ranch:

Through every window the out‑of‑doors comes right up to me. There is this ever changing great sky and the desert below and the dark line of the Rio Grande. I never get tired of seeing it. And my past life is spread out before me like this great view. Now I am old I can look over it as I do from this mountainside over the valley below. I have known love and passion and ecstasy and hate and pain, but now there is peace in me . . . . (Memoirs and Correspondence, 133)

She has also been the subject of several biographies, herself. Like Lawrence, Frieda defies neat categorization; however, she was an individualist who lived the unorthodox kind of life she wanted. As a proto‑feminist, Frieda "had no feminist framework in and through which to articulate her struggle," says Jackson, "nor did she see the need for one" (65). Nonetheless, she arrived at similar goals through her own unique path. Frieda died of a stroke at her El Prado home on her 77th birthday, August 11, 1956. She had requested to be buried just outside the Lawrence Memorial and for a farewell ad to be placed in El Crepuscolo, a Taos newspaper edited by Johnson, thanking all her friends for their friendship‑‑and signed: Frieda Emma Johanna Maria Lawrence Ravagli. The ranch service took place on August 13 and included a reading of Psalm 121 ("I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills . . .") and Lawrence's poem "Song of a Man Who Has Come Through."

Narrative by Tina Ferris & Virginia Hyde

(2004)