Historical Significance Narrative -- LAWRENCE IN AMERICA

National Register Nomination for the D.H. Lawrence Ranch

SECTION 8: Narrative Statement of Significance, Continued

4. Lawrence in America

Arriving in San Francisco in September of 1922, the Lawrences took the train to Lamy Station (near Santa Fe), New Mexico, where they were met by their new hostess, the art patron Mabel Dodge (still Sterne at this time). She had previously sent the Lawrences enticing letters praising the pristine quality of Taos and including samples of Indian medicinal roots, aromatic herbs, and jewelry. Mabel had been attracted to Lawrence's writing, having read his travel book Sea and Sardinia (1921), and was hoping he would write similarly of the Southwest and its pueblo life. The Lawrences spent the first night at the Santa Fe home of the poet Witter Bynner, who later reported having been "drawn and held by their magnetism" that evening (Bynner 6). They then moved into an adobe house Mabel had built next to hers in Taos. Lawrence turned 37 years old the same day.

Mabel wasted no time in arranging for Lawrence to attend the Apache harvest festival at Stone Lake, New Mexico, and the San Geronimo festival at Taos Pueblo. His first impressions were turned into the articles, "Indians and an Englishman" and "Taos," both published in the Dial in 1923. Mabel also supplied Lawrence with details of her life and background for a semi‑biographical novel he was to begin and never finish. She arranged nightly gatherings of stimulating conversation and entertainment similar to those of her earlier Salon days in Greenwich Village. And she introduced Lawrence to the controversial Bursum Bill, enlisting his aid in the Indian cause over land and water rights. Thus Lawrence took an active role in U.S. politics with his article "Certain Americans and an Englishman," advocating the bill's defeat.

As Lawrence states in the opening lines of his essay, he had arrived in the Southwest "at a moment of crisis," and he sits down "solemnly" to study "the Bill" from beginning to "distant end" (18):

The Bursum bill plays the Wild West scalping trick a little too brazenly. Surely the great Federal Government is capable of instituting an efficient Indian Commission to inquire fairly and settle fairly. Or a small Indian office that knows what it’s about. For Heaven's sake keep these Indians out of the clutches of politics. Because, finally, in some curious way, the pueblos still lie here at the core of American life. (New Mexico, 20)15

Prior to the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, Native Americans were considered legal wards of the federal government. In a later poem entitled "O! Americans," Lawrence called upon U.S. citizens to display "noblesse oblige" toward the American Indian and culture, "the one thing that is aboriginally American." He says it is our "test" whether or not we can "leave the remnants of the old race on their own ground,/ To live their own life, fulfil their own ends in their own way" (Poems, 776, 779). But at the same time he was against sentimentalizing the "Red Men" or holding them back for the profit of artisans.

John Collier (U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1933‑1945) lived next door to the Lawrences around this time. Together they had intensive discussions regarding the fate of the pueblos and the value of preserving ancient Amerindian religions with their instinctive wisdom and interconnectedness. Taos Pueblo scholar, William Wilbert, states that Collier was "thoroughly exposed to Lawrence's thoughts on the future of the native people of the Americas" and considers both men to be "prophets of American Indian restoration" (10, 1). Lawrence's concerns were poured into the prose of his "American art" while Collier's became political action. Collier's first initiative was to push through Congress the Indian Reorganization Act that granted cultural, religious, and economic freedom to all Native Americans and secured his reputation as "the best Indian commissioner in our nation's history" (Waters, 88). Collier also organized in 1940 the First Inter‑American Conference on Indian Life held at Patzcuaro, Mexico, with delegates from the U.S. (including Tony Lujan) and Latin America; and he became president of the Inter‑American Indian Institute. The fruit of Collier's interest in Indian welfare can be traced directly to the germ of these Taos discussions. When later asked about the Taos Indian perception of Lawrence, Collier replied, "The Indians liked Lawrence, and so he must have understood them." He told how a group of mourners from Taos Pueblo journeyed to Kiowa Ranch to pay tribute to Lawrence when they heard he was dead. Collier further commented that "Lawrence essentially was a gentle, kindly and unaggressive individual" and hence the Taos Indians "accepted him" (Nehls 2:199, 198).

Lawrence's voyage to America coincided with another point of crisis in his own career: the New York case against Women in Love brought by an organization called the Society for the Suppression of Vice. His American publisher Thomas Seltzer defended the novel and won. The resulting publicity helped promote Lawrence in the United States by increasing sales. Magazines, such as the Dial, Smart Set, Forum, and Poetry, also played a vital role in establishing his American audience. Smart Set had one of the highest circulation figures of the time among the literary avant‑garde. Forum was the first to publish Lawrence in America (1913) and later boldly accepted some of his more controversial pieces. Poetry published 27 of his poems between 1914 and 1923. As a primary outlet, the Dial consistently published Lawrence in a variety of genres‑‑30 works and numerous reviews of his writing‑‑throughout the 1920s. Success in the illustrated "glossies" such as Vanity Fair, Travel, and Theatre Arts Monthly was a further boost to his career. The American market would eventually help substantially to lift the burden of financial worries that had plagued him in Europe. Lawrence was entering a prolific phase, and more works would be published overall during his American period than at any other time.16

Soon Lawrence was buying cowboy apparel, learning to ride horseback, and exploring the "high desert." The New Mexico landscape had a tremendous impact on him. He wrote in a letter to his sister Emily King dated March 31, 1925: "I really like this country better than any landscape I know‑‑the desert and mountain together" (Letters 5:228). However, his independent nature began to clash with Mabel's strong‑willed agendas; and Lawrence disliked the smothering aura of indebtedness. His creativity could not be ordered about; he felt too much under "the Wing" of Mabel (Letters 4:335‑336).17 To preserve friendly relations, the Lawrences sought out other living arrangements.

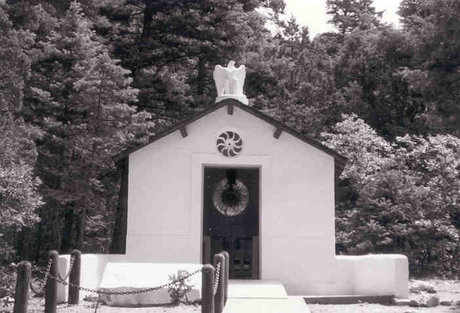

At the beginning of November, 1922, they had a trial stay at Mabel's Flying Heart Ranch on Lobo Mountain, the same which they later owned and renamed Lobo, then Kiowa after the ancient Indians who had camped there. The idea was that if they liked it, they would pay Mabel rent. Lawrence reported in a letter, "It's a wonderful place, with the world at your feet and the mountains at your back, and pine‑trees" (Letters4:334). Finding the ranch in poor condition, however, and with cold weather fast approaching, the Lawrences temporarily moved to the nearby Del Monte Ranch (owned by the Hawk family), where they entertained guests during the course of the winter: Lawrence's agent, Robert Mountsier; his New York publisher and wife, Thomas and Adele Seltzer; and the Danish painters, Knud Merrild and Kai Gotzsche, who lived all winter on the ranch. Lawrence enjoyed painting along with the Danes,18 creating illustrations and cover designs for his works, including his poetry book, Birds, Beasts and Flowers (1923). This collection features such Southwestern poems as "Eagle in New Mexico," "Men in New Mexico," "Autumn at Taos" (Text Appendix 1), "The Red Wolf," "Mountain Lion," "The Blue Jay," "Spirits Summoned West," and "The American Eagle." Plans were also made for Lawrence's first visit to Mexico, which began in spring of 1923.

Along with Bynner and Willard "Spud" Johnson, Lawrence and Frieda toured Mexico from March to June, ending up in Chapala where Lawrence wrote Quetzalcoatl, the first version of The Plumed Serpent (see the published book-cover in Appendix Q). Thus the "American novel" Lawrence had envisioned writing was to be set in Mexico (Letters 4:457). Frank Waters, author of acclaimed texts about Pueblo Indians and reputed "Grandfather of Western Literature," comments: "Though the book was not laid in Taos, it transported Taos Pueblo and everything Lawrence had learned about its Indians to Mexico. It is all there‑‑their dress and customs, dances, songs, the very drumbeat" (87). Lawrence wrote, "It interests me, means more to me than any other novel of mine. This is my real novel of America" (Letters 4:457.)

Although the Lawrences wished to return to Taos and the ranch, the thought of another rough winter at high altitude was overruled by the lure of family and friends back in England. Still, Lawrence was reluctant to leave; and, after a quarrel, Frieda traveled on ahead with Lawrence following three months later.19 Once there, however, Lawrence loathed the dead and claustrophobic feeling of his postwar homeland.20 He soon began making plans for a return to America after completing his round of visits in Europe.

Lawrence called his friends together for a dinner at the Café Royal in London and asked them to join him in the adventure of making a fresh start in America. The invitation was reminiscent of his "Rananim" plan devised back in 1914, the name taken from a Hebrew song ("Rejoice") and related to a word meaning "green, fresh, or flourishing."21 Depression over the war, coupled with a low point in his career, had made Lawrence yearn for a "clean break" and a sense of community founded on "decency" to alleviate his feelings of isolation. In a 1915 letter to his Russian friend S.S. Koteliansky, Lawrence says, "We are going to found an Order of the Knights of Rananim" (Letters 2:252). He describes a flag that is to have a scarlet ten‑pointed star on a black background and sketches out a heraldic badge with his symbol of a phoenix rising from the flames. A metal plate with this same phoenix design would later hang on the Lawrence tree at the Kiowa Ranch, keeping alive the spirit of Rananim. However, the only friend from those gathered at the Café Royal who was sincerely committed to going with the Lawrences to the New World, was the Honorable Dorothy Brett, a gifted painter and daughter of the second Viscount Esher.

Narrative by Tina Ferris & Virginia Hyde

(2004)