National Historic Register Nomination -- End Notes

National Register Nomination for the D.H. Lawrence Ranch

NOTES

1Lawrence had two arm‑chairs, both built in 1924. One he built himself, shaped with a hand‑ax and carved with a penknife (Brett, 122). Both Frieda Lawrence and Mabel Dodge Luhan describe it‑‑a "rough" piece of furniture, says Frieda in "Not I, But the Wind..." (v); a "delicate, decorous chair," says Luhan in Lorenzo in Taos (212). Frieda says she embroidered a piece of petit point for this chair, and Lawrence himself sometimes stitched it (v), but this piece has not survived. Mabel also built a chair for Lawrence, modeling it in the wide, deep, and heavy Spanish style she describes, apparently like a Spanish Colonial "priest's chair" which derived from Romanesque thrones. She painted it pale pink with "touches of green in the carving," and Lawrence jokingly referred to it as the "Iron Maiden" (Luhan, Lorenzo in Taos, 202, 203). It appears possible that the chair displayed at the ranch is the latter.

2Brett tells how the Taos Indians used this term (89), but Witter Bynner suggests, instead, that it was "Red Wolf" (8); in reality, both names were probably used since the fox and wolf belong to the canine family. The Taos Indian nickname for Frieda was "Angry Winter" (Brett, 89).

3Ravagli returned to Italy in 1960 and died in 1976. The red fox statue now adorns Ravagli's memorial at a cemetery in Spotorno, Italy, as recently confirmed by Stefania Michelucci (5).

4"The Spirit of Place" is the name of the opening essay in his Studies in Classic American Literature. The earlier, more idealistic, versions of these studies were collected by Armin Arnold in 1961 under the titleThe Symbolic Meaning and they will be included in the Cambridge Edition of SCAL.

5Lawrence tells how Rananim was first planned late in 1914 (Letters 2:268)‑‑and he directly cites the song version of "Ranani Zadikim Zadikim l'Adonai" ("Rejoice in the Lord, O ye righteous," Psalm 33:1), referring to the psalm as sung by Koteliansky. A link seems likely, too, with the Hebrew adjective "ra'annanim" (green, flourishing) from Psalm 92:14 (K. W. Gransden, 22‑32).

6E.W. Tedlock, Jr., later edited her Memoirs and Correspondence; see also Michael Squires, D.H. Lawrence's Manuscripts, containing correspondence between Frieda and the bookseller Jake Zeitlin, and others, and revealing significant details of the dispersal of the Lawrence manuscripts over a period of 30 years.

7See both the first and second editions of Gilbert’s Acts of Attention; Shapiro’s statement is in his personal letter (1985), in Legacy (Reference List).

8Other Lawrence organizations include Phoenix Rising of New Mexico, the D.H. Lawrence Society of England, the Rananim Society, the Haggs Farm Preservation Society of England, and the D.H. Lawrence Societies (besides those named in the text) of England, Japan, Korea, China, Australia, and Italy. In Iida's book, writers discuss the lively Lawrence circles and scholarship in Britain, the United States, France, Italy, Germany, Poland, Finland, Mexico, Canada, Australia, Japan, Korea, China, and India. International Lawrence conferences have been held in diverse locations, including Boston, Shanghai, Montpellier, Ottawa, Nottingham, Paris, Taos, and Naples. The next two are scheduled for Kyoto and Santa Fe.

9The Modern Language Association of America has also published a new book presenting numerous ways of teaching Lawrence’s works (see Elizabeth Sargent and Garry Watson in the Reference List).

10On this largest collection, in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, see Roberts, 23‑37. In addition, the UNM Lawrence collection includes a number of items by both D.H. Lawrence and Frieda Lawrence. Included, for example, are typescripts of some of the essays in Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine. The University of California (Berkeley) also has significant Lawrence manuscripts and typescripts; and among other Lawrence repositories in the United States are libraries at Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Cornell, Duke, Stanford, UCLA, Northwestern, the University of Illinois, and the New York Public Library. (There are still a few private collectors, as well.) Of course, the University of Nottingham has an excellent collection of Lawrence manuscripts, typescripts, and art works as well as the renowned D.H. Lawrence Centre.

11Some of the other literary journals devoted to Lawrence include Études Lawrenciennes (University of Paris), Journal of the D.H. Lawrence Society (Eastwood, England), D.H. Lawrence Studies of Kyoto(Japan). D.H. Lawrence Studies (Korea), Rananim (Australia), and the recently announced (2000) Quaderni Lawrenciani (Italy). The Newsletter of the D.H. Lawrence Society of North America is edited at the University of Maine (Presque Isle) by Eleanor Green.

12The book is a 1915 first edition of The Rainbow with the Frank Wright book jacket.

13Helen Croom (Bristol, England) is the owner of an academic listserve as well as the Rananim listserve; for the latter, Tina Ferris (Diamond Bar, California) and R. H. Albright (Boston, Massachusetts) are the Moderators. Charles Rossman, Professor of English at the University of Texas (Austin), was the originator of the academic service.

14See Peter Preston, 28, recording that 1990‑1991 was the first year in which the number topped 10,000. The Broxtowe Borough Council had purchased the property for the Visitors' Centre and shop in the former year.

15This essay, like others by Lawrence on Native Americans, will be in the Cambridge Edition ofMornings in Mexico and Other Essays. The texts have been established through examination of the surviving manuscript and typescript material from Lawrence's New Mexico period.

16Referring to 1923, for instance, Warren Roberts, James T. Boulton, and Elizabeth Mansfield, editors of Lawrence's letters of that period, state that "never before or afterwards were so many Lawrence books published in so short a time" (Letters 4:18). One reason for the flurry of publications was the enterprise of Lawrence's new American publisher, Thomas Seltzer (from 1920 to 1924). According to the same editors ofLetters 4: "Altogether, twenty of Lawrence's books appeared with the Seltzer imprint, and of eight major works published between May 1921 and March 1923 only one was published first in England" (2). Another five Lawrence books appeared in 1924‑1925 during the remainder of the American period and five more were completed and near publication by the time he returned to Europe. See also Nicholas Joost and Alvin Sullivan on The Dial and Sharyn R.Udall on Laughing Horse.

17This letter to his agent Robert Mountsier on Nov. 6, 1922 (among other letters) tells in detail of his desire to go to the ranch and to invite others there. But see John Turner and Worthen, distinguishing between this plan and the earlier one of Rananim (135‑71).

18See especially Knud Merrild and David Ellis.

19After Frieda's departure, Lawrence journeyed west again, reuniting with the Danish painters, Merrild and Gotzsche, in Los Angeles, then rambling with Gotzsche through western Mexico and eventually to Vera Cruz. In Mexico, he wrote his co‑authored novel, The Boy in the Bush (with Mollie Skinner), published in 1924.

20Upon his arrival in cloudy London, he sent "Spud" Johnson an essay of exultant praise for the sunny Southwest and its free-kicking spirit ("Dear Old Horse, A London Letter"), intending it as the first in a series of travel pieces for Johnson's Laughing Horse. Only one other of this group ("Paris Letter") was published in his lifetime, but a third, "Letter from Germany," appeared in 1934.

21 See note 5 above.

22"Diary" notebook (1920‑1924), in Tedlock's Frieda Lawrence Collection, 98. This notebook, now in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin, contains notes about finances along with manuscript versions of some of the poems for Birds, Beasts and Flowers.

23Lawrence had dismissed Mountsier in February 1923 and had no American agent until the following spring, when the English agent Curtis Brown began to handle Lawrence's American market as well as the English.

24Lawrence was at this time at the height of his "Pan cluster," comprising the century's most notable revival of the "all" god (see Patricia Merivale, 194‑219). Lawrence envisioned not simply Pan's resurrection in the New World but his survival here from primordial times despite his legendary "death" in the Old World. On St. Mawr, see also James Cowan, American Journey, 90‑96; and Charles Rossman, xiii‑xxxii.

25The title, as published in Johnson's Laughing Horse, contained these last two words "Tired Out," but Lawrence's own manuscript and typescript do not. It is probable that the Cambridge Edition of Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, including this piece, will use the shorter title.

26The other essays include "The Future of the Novel" (published in 1923 as "Surgery for the Novel‑‑or a Bomb"), "Why the Novel Matters," and "The Novel and the Feelings" (both written in 1925 but unpublished in Lawrence's lifetime).

27In 1929, for example, Lawrence was still deeply concerned with affairs at the ranch, writing Brett about the importance of ascertaining its boundaries: "Glad you had the rights of the ditch fixed. One day, when you can get a chance, do try and get someone to fix the real boundaries of the ranch‑‑locate them, I mean. If some old‑timer can remember the corner‑tree, then you can take the sights. Old Willie Vandiver [the blacksmith at San Cristobal] might know. You know the ranch‑property is really a square, and is quite a bit bigger than the present enclosure. And the piece above the house, up towards the raspberry canyon, is really inside the bounds, and I should like that secured especially, as it keeps us private. If we could find out the corner marks, we could fence bit by bit" (Letters 7:506).

28Although there has been controversy about the authenticity of the ashes, Lawrence's Cambridge biographers have found their papers in order.

29In Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious (1921, 1922), however, Lawrence quarrels with Freud, disassociating himself from Freud's ideas of the incest motive in the unconscious. Although Lawrence never lived to see revisions of Freud by Jacques Lacan and others, some critics today read him in terms of post-Freudian stances (see, for example, Cowan, Trembling Balance; Earl Ingersoll; and Margaret Storch, Sons and Adversaries). Of course, Lawrence was interested in investigations of unconscious motivations in literary tradition, itself‑‑in such modes as drama, dramatic monologue, first‑person narration, free indirect discourse, and "stream of consciousness."

30In a letter to Richard Aldington, Frieda uses similar imagery for Lawrence: "I see him in the tradition of . . . Francis of Assisi with Lorenzo's [Lawrence's] almost uncanny love for animals and plants" (Frieda Lawrence and Her Circle, 88).

31See also Robert R. White, Patricia Janis Broder, Sherry Clayton Taggett and Ted Schwartz, and Luhan, Edge of Taos Desert and Taos and Its Artists.

32Dates for these books are as follows: Bynner, 1951; Merrild, 1938; Foster, 1972; Luhan, 1932. Merrild's was later reprinted with another title: With D.H. Lawrence in New Mexico: A Memoir of D.H. Lawrence (1964). See also Lois Rudnick on Luhan.

33Brett's portraiture is shown, for example, in the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Gallery, London; the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts; the Metropolitan Museum, New York; Boyer Gallery, Philadelphia; Denver Art Museum; and Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. Frank Waters particularly praises her paintings of pueblo ceremonials, stating that the "heyday of Indian dancing" is forever "framed in her gorgeous paintings" (150). See also Hignett.

34See also Rachelle Katz Lerner, 79‑94, on Lawrence and William Carlos Williams.

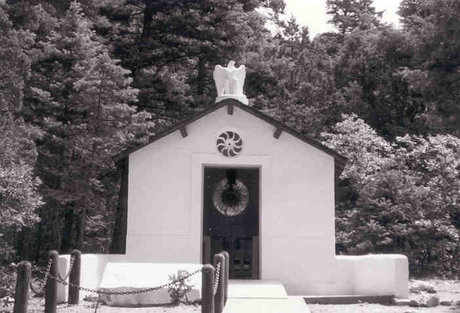

35See Louis L. Martz, "H.D. and D.H.," 126‑128, on ties between the Taos memorial and the temple in H.D.'s poem, itself reflecting the Egyptian temple in Lawrence's novella The Man Who Died (first published in a short version, The Escaped Cock, a title which is, today, often used for the entire tale). In a letter, Frieda confirms the likeness between the fiction and the actual ranch shrine as created by Ravagli and herself: "We have made a lovely place on the hill, a bit like the little temple of Isis in 'The Escaped Cock'” (Frieda Lawrence and Her Circle, 69).

36See also Evelyn J. Hinz and John Teunissen in their Introduction to Miller's The World of D.H. Lawrence, 24. Miller also wrote a second book on Lawrence, compiled late in his life from his extensive notes: Notes on 'Aaron's Rod' and Other Notes on Lawrence from the Paris Notebooks.

37Personal letter from Shapiro (1985), in Legacy, 8.

38See Neal Bowers, 11‑12.

39Personal letter from Bly (1985), in Legacy, 9.

40Creeley is, of course, making a pun, referring not only to the British currency but also to Ezra Pound, who so substantially edited T.S. Eliot's The Wasteland that he has been credited with some of its distinctive features. Pound was an early supporter of Lawrence's poetry.

41The central characters in Boyle's Year Before Last and "The Rest Cure" are believed to be based partly on Lawrence, the latter drawing upon details of his last illness and death (see also Leo Hamalian, chapter 6).

42LeSueur identified deeply with The Man Who Died and was attracted to Lawrence's working‑class origins, his passion for the earth (influencing her descriptions of the Midwestern United States), and his fertility themes, including the mythology of Persephone (see Hamalian, chapter 4).

43Millett's Sexual Politics, at the end of the 1960s, was most hostile; Simpson provided important historicity; Gilbert’s “Preface” and Siegel’s book consider the literary influence of women writers on him and his on them. This present narrative takes into account more than 20 women writers and critics, from memoirists of the 1930s like his boyhood companion and sweetheart Jessie Chambers (E.T.) to a recent biographer who casts him as preeminently the "married man" (Brenda Maddox, whose book is entitled The Married Man in England).

44See also note 29 above.

45Manchester Guardian, 12. Alastair Niven once even made the claim that Lawrence is "the most widely studied author in the English language" after Shakespeare ("D.H. Lawrence: Literary Criticism and Recent Publications," British Book News [September 1985]), as reported in Legacy.

46While Lawrence was proclaimed a "guru" by some of the "hippie" movement, who displayed posters of him at "sing‑ins" and "love‑ins," writers on Lawrence frequently point to the irony that he was claimed by a movement with which he would have felt so little in common. His late essay "A Propos of Lady Chatterley's Lover" contains a ringing defense of "Marriage sacred and inviolable, the great way of earthly fulfilment for man and woman" (Lady Chatterley's Lover, 321‑322). This essay was cited during the English trial by clergymen and other expert witnesses.

47The first of the trials (1950‑57) had actually been in Japan, where the case brought against Oyama Publishing Company resulted in a restrictive decision that has, however, not been enforced in recent time (see Iida, "The Reception of D.H. Lawrence in Japan," 240‑4).

48A report that Brett did not attend (for example, Sean Hignett, 260) is erroneous, for she appears in conference photographs. She was then 86 years of age and would live to be nearly 94, dying on August 27, 1977. Her ashes are scattered on the "Pink Rocks" below Lobo Mountain (see Hignett, 262‑263, 270).

49See note 8 above on the other International D.H. Lawrence Conferences sponsored in part by the DHLSNA.

End Notes by Virginia Hyde & Tina Ferris

(2004)